How to solve the Secret Santa Problem using graph theory

Let’s talk about graphs, Hamiltonian cycles, NP-problems, and backtracking search.

Every year we have a Secret Santa event in our family. Instead of giving a crappy cheap gift to every family member, we assign receivers randomly, so everybody gets one good and valuable present from an anonymous Santa.

We decided to develop a simple website where every family member can sign up, fill their wishlist and get a receiver’s name when the event starts. There are many websites and apps for this, but we decided to have our own service to add some modifications to the sorting algorithm.

After every participant has registered, we need to run a sorting algorithm to decide who gives a present to whom. To solve the Secret Santa Problem we need to find this sorting algorithm.

We have an array of all participants. Let’s take the first one by random. Let’s say we have Bob. Next, we remove Bob from the initial array and get a random participant from it. Let’s say we get Alice. So, Bob gives a present to Alice. Then remove Alice from the array and get a random participant who will become a receiver for Alice. And so on. Repeat until the initial array is empty. The last participant will be the Secret Santa for Bob, who was first. The chain of Santas is complete.

Such an algorithm is called naive. Each step is obvious, and it imitates people taking tokens from a hat or a lottery machine. In most cases, naive algorithms are not optimal and don’t have great performance, but this task is so easy that the naive algorithm is optimal and has O(n) performance and O(1) memory.

The next step is to modify the problem and add some additional requirements to our algorithm. This is why we wanted to create our own service. Sometimes with pure random you can get a Secret Santa who cannot be secret for some reason. E.g., if my Santa is my wife, it is almost impossible to keep it secret.

So, we decided to add constraints to the problem. For example, Alice and Bob sign in to the event but don’t want to give each other gifts. We need to add this data to the algorithm and take these constraints into account. We can slightly modify the algorithm: when we need to pick a receiver for a participant with constraints (e.g., Bob), we remove these constraints (Alice) from the pool of participants and pick a random one just as before.

With such constraints our naive algorithm can fail in some cases. What if it is the last step of the algorithm, we need to pick a receiver for Bob, and Alice is the only option left in the pool? In this case, if we apply all the constraints, there will be no options to pick, and therefore there will be no solution.

How can we solve it? The simplest way here is to restart the algorithm until we get a solution. If there are few constraints, it should be pretty safe. Actually, we fixed it exactly this way in the first version of the web-service. It works really well for 10 participants and a couple of constraints and finds a solution in one run. Sometimes it needs 1 or 2 restarts, but there are no infinite loops.

But this is a dirty solution to our initial problem. Let’s find a proper algorithm that solves this problem for any input data. Probably, we need to use another representation of it.

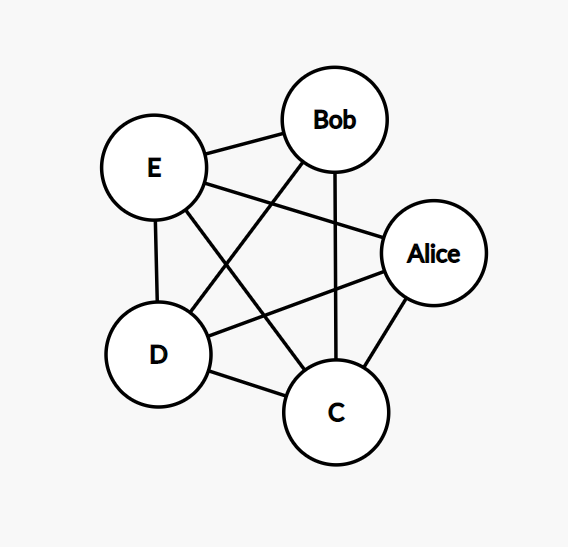

We have participants. We also know constraints (if any) for participants who don’t want to give presents to each other. When we have some objects and connections between them, it’s time to think about graphs.

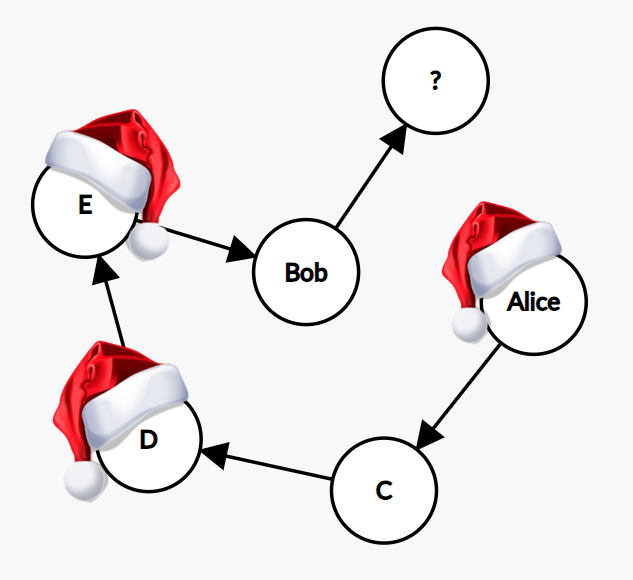

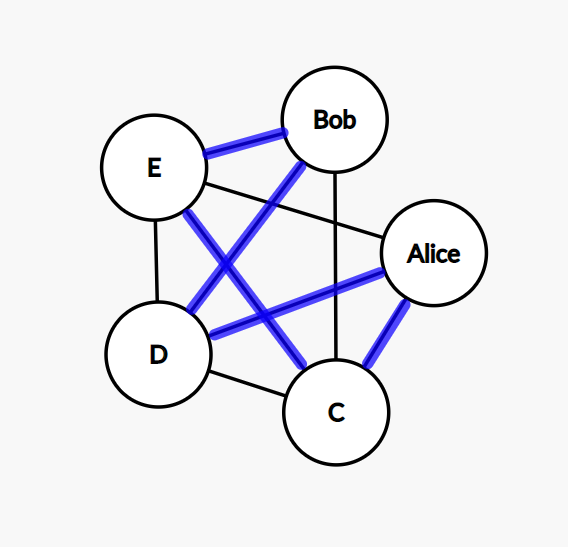

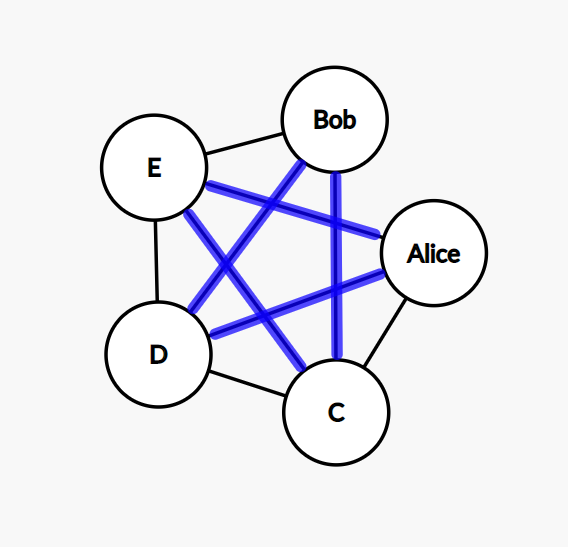

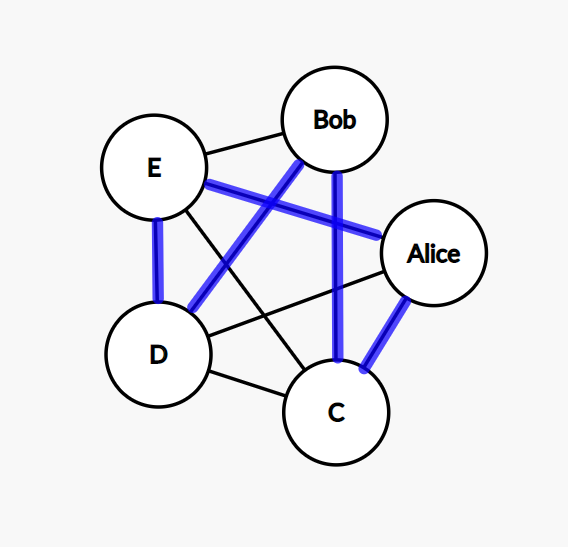

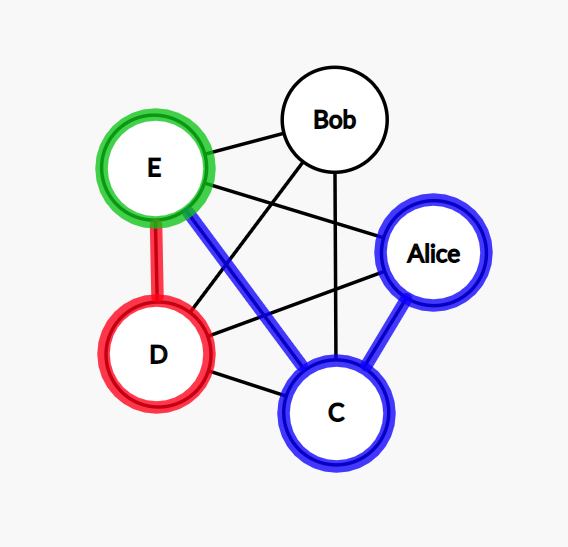

In this picture, nodes are participants, and connections between nodes show that they can give each other presents. Bob and Alice cannot do this, so there is no direct connection between them.

Now we can see that our solution is a path on this graph. It must start with any node, then go through each other node exactly once, and then go back to the beginning, so it means the path is actually a cycle. A path that goes through all nodes exactly once called a Hamiltonian path. Consequently, such a cycle is a Hamiltonian cycle.

This means that the Secret Santa Problem is basically a Hamiltonian cycle problem, and we can find the right algorithm in a book or on the internet.

Ok, Google, how to find a Hamiltonian cycle in a graph?

But Google disappointed me. Apparently, there is no fast algorithm to find a Hamiltonian path or cycle in a graph. This is an NP-problem (nondeterministic polynomial), which means there is no polynomial algorithm for it.

The more famous (or notorious) NP-problem is the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP for short):

Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, what is the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and returns to the origin city?

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? We need to visit each node exactly once and return to the initial node. This is basically a Hamiltonian cycle we have here. The TSP doesn’t have a fast solution. People write scientific papers about how to solve it faster. Some use heuristics to reduce the number of options in brute-force search. Some use dynamic programming to split it into subproblems, which are easier to solve.

Does it mean our Secret Santa Problem requires such a complex algorithm? No, it’s much easier. The main difference here is that the Traveling Salesman Problem requires an optimal Hamiltonian cycle (shortest or most profitable) and the Secret Santa Problem requires any Hamiltonian cycle.

To brute-force the TSP, we need to find all the possible cycles and pick the optimal. The amount of possible cycles is calculated with the factorial function: multiplication of all integers from 1 to N. If we have 5 nodes in a graph, there will be 120 cycles to brute-force. For 10 nodes, there would be 3628800 options. For 20 nodes: 2432902008176640000. That’s a lot.

Our problem is much more simple. There are many suitable cycles in the graph, and we need to find the first suitable. Brute-force is not that scary now.

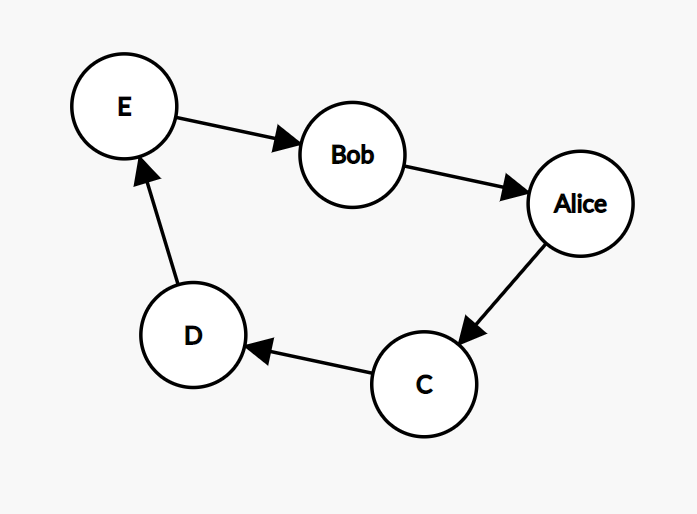

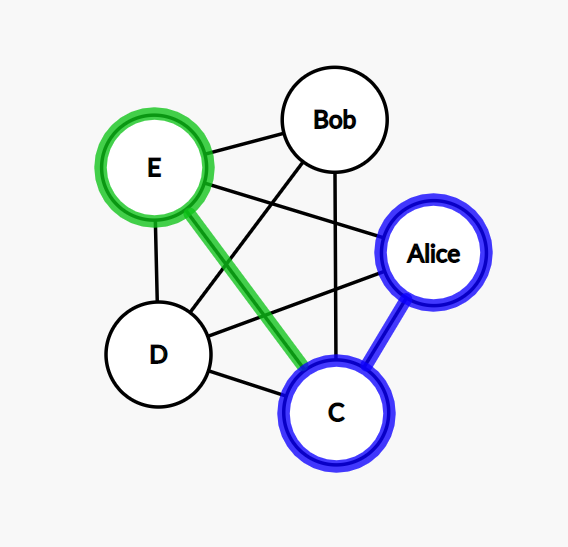

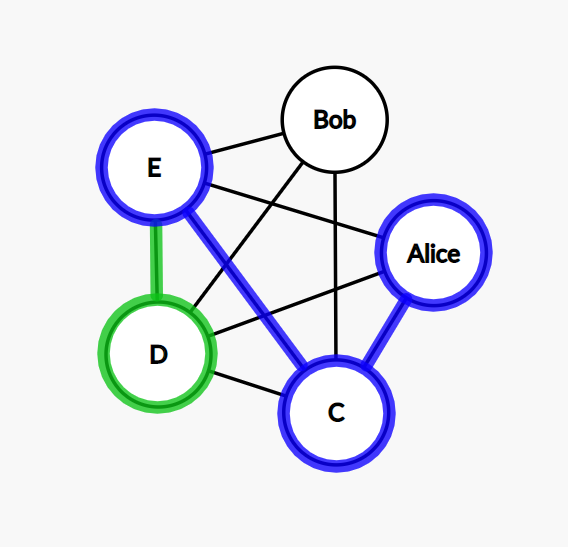

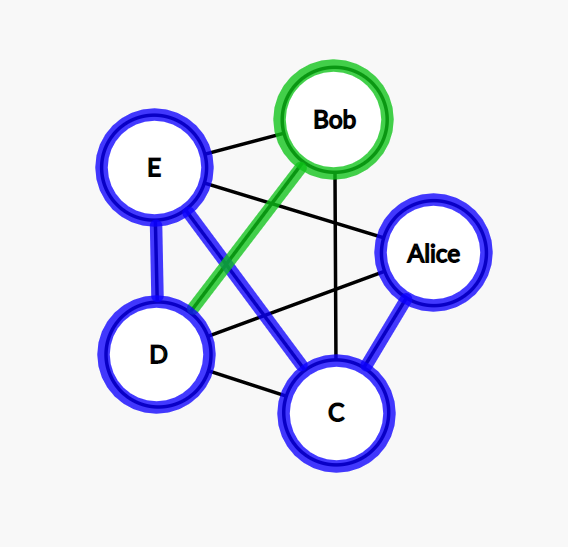

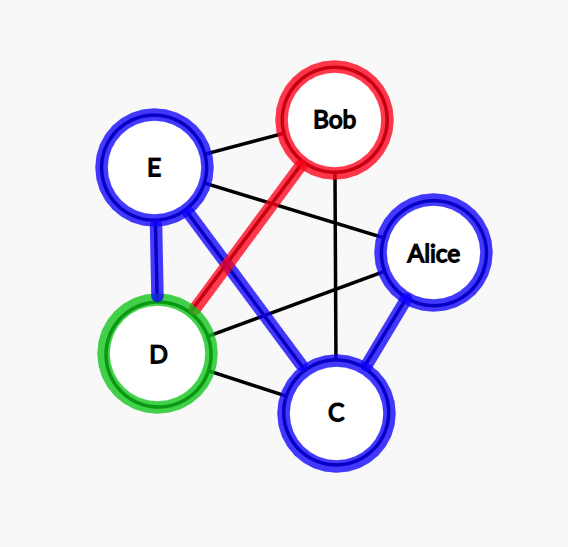

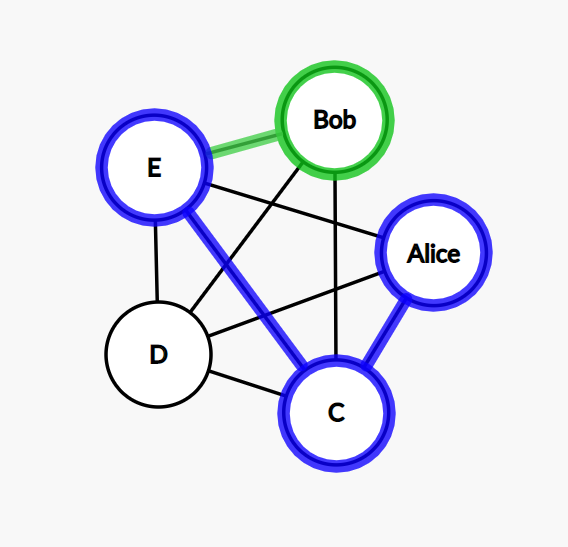

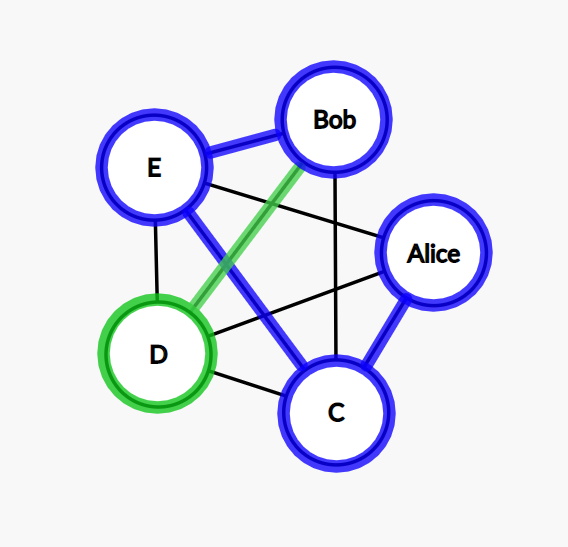

Here are 3 examples of Hamiltonian cycles in the graph for Alice, Bob, and their friends.

Let’s figure out the algorithm. Our goal is to find a Hamiltonian cycle in the graph using brute-force. We start with a random node. This node has some connected nodes. We pick one of its neighbors at random and go there. This node has connected nodes too. We pick one of them which hasn’t been visited yet. And so on.

At some steps, we can find out that there are no available nodes to pick. It might happen if there are no more connections (because of constraints) or if all neighbor nodes have been visited already. This issue looks like the issue we had with the naive algorithm. With a graph, it’s more clear that we can do a step back and pick another random node. If we did a step back and there are still no nodes to pick, we do another step back.

Repeat until we visit all nodes and return to the first one. The cycle is complete.

Such a search is called backtracking search or depth-first search.

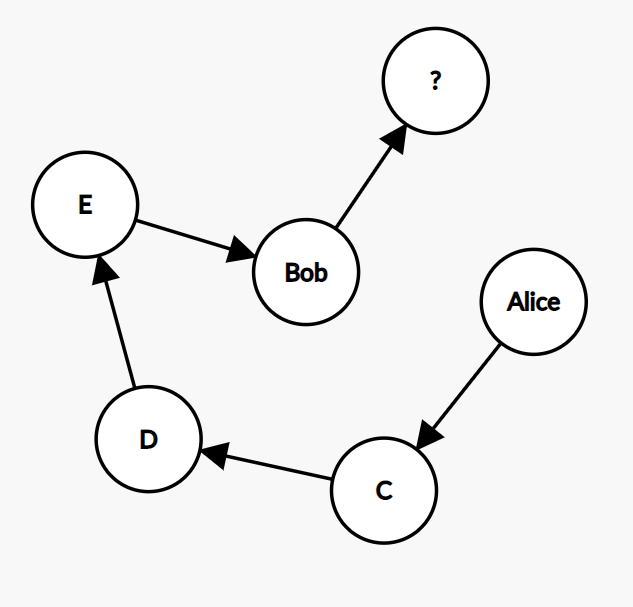

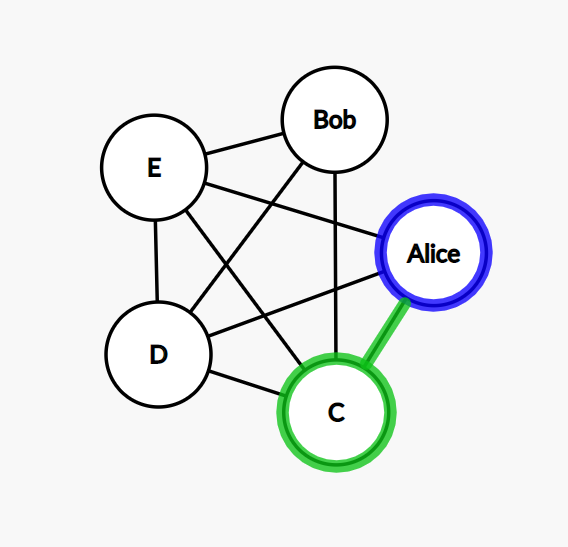

Let’s see an example.

Step 1: we start with Alice and pick the next node at random. We get the node C.

Step 2: the node C is connected to E, D, Bob, and Alice. We exclude Alice because this node has been used already. We pick E at random.

Step 3: then we pick the node D.

Step 4: the only node left to go from D is Bob. All the other nodes have been visited already.

Step 5: our path contains all the nodes, and we need to go to the node Alice and finish the cycle, but there is no connection between Bob and Alice. We need to do a step back, so we return to D.

Step 6: remember, we could only go to Bob from D at step 3, and we already know that this path doesn’t lead to a solution. So we need to do yet another step back and return to E.

Step 7: this time, we go from E to Bob.

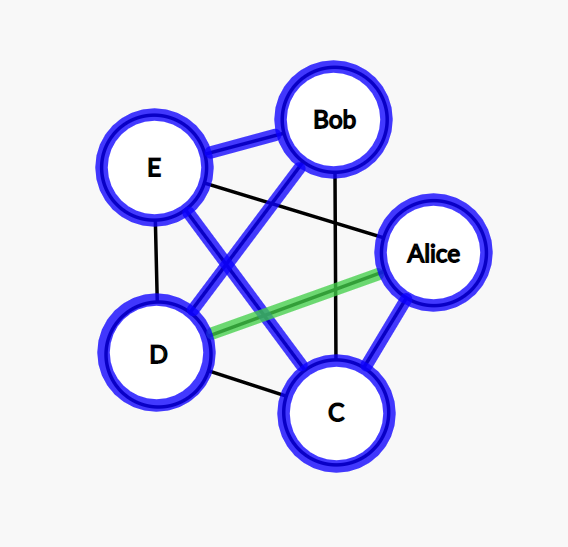

Step 8: the only possible move is from Bob to D now.

Step 9: we can go from D to Alice now. The cycle is complete. We found a solution.

If we always find a dead end and, after multiple backtrackings, we returned to the first node without any success in finding a Hamiltonian cycle, then there is no solution for this graph. This is the worst possible case because we need to brute-force all the paths to verify that there is no suitable cycle. And it’s a lot, remember the factorial function.

But we are solving the Secret Santa Problem for a particular web-service. It’s actually an engineering task, not a math one. It is only possible to fail the algorithm if there are too many constraints, and there are not enough connections in the graph to find a proper cycle.

It would be suspicious if we had a Secret Santa event, and some participants decided that they don’t want to see almost all other people as their Santas. We can add some limits to the interface and define that each participant can have 3 constraints at max. This must be enough for everybody, and it will prevent the algorithm from brute-forcing millions of paths.

I did some tests. With 3 constraints algorithm sometimes has to do 1 or 2 backtrackings, but for most cases, it finds a solution in N steps for N participants. With a larger amount of constraints, it gets worse. E.g., with 100 participants and 50 constraints for each, brute-force sometimes requires 100 steps, sometimes 400000, and sometimes 1500000.

Our initial problem is solved, and we have a working web-service with a stable sorting algorithm. It works fast enough even with thousands of participants, which is more than enough for a family-scope event. And we learned something about Hamiltonian cycles, NP-problems, and depth-first backtracking search.