How to write your own compiler and executor for mathematical expressions

Let’s talk about infix, prefix and postfix notations, abstract syntax trees, and how to convert a human-readable expression into a computer-digestible form.

Sometimes we need our programs to be able to run simple mathematical expressions entered by a user. E.g., it can be an arithmetical expression in a command-line calculator, an expression to process a result of analytical device measurements, or it can be an expression to calculate scores for a player in a videogame. Languages for such expressions are sometimes called scripting languages or domain-specific languages.

A user enters a human-readable expression as a string. The program then has to parse it, convert it into a form understandable by a computer, and then execute it with some data. Unfortunately, expression notations for humans and computers are usually different and require translation.

Infix notation

Let’s start with a simple expression: 1 + 2. It is a mathematical operation that sums two numbers. The + sign is an operator; it shows what action we need to do. 1 and 2 are operands; they are objects what our operation works with. The same is true for logical expressions too, e.g., A or B.

When we use arithmetical or logical expressions, we usually put operators between operands if we assume that humans will read these expressions. It is called “infix notation”: the operator is INside the expression.

It is the expression notation we all have got used to, but it has a couple of disadvantages. First, we need to take care of operation priorities if we have multiple operators in a single expression. E.g., multiplication is stronger than addition. In the expression A + B * C, we calculate B * C first and then add its result to A. If we want to change the order and calculate the sum first, we need to use parentheses (round brackets): (A + B) * C.

Second, infix notation isn’t the best notation if we want to teach a computer to execute mathematical expressions mainly because the order of execution is not the same as reading.

Prefix notation

Prefix notation, also known as Polish notation or normal Polish notation, is when we put the operator before its operands. 1 + 2 becomes + 1 2. A or B becomes or A B. Humans haven’t got used to it, so it might look a bit strange or difficult. It gets even worse if we have expressions with multiple operators, e.g., A and B or C becomes or and A B C.

The basic idea is that we read tokens from the expression one by one. If it’s an operator, then we continue reading until we have enough operands for it and execute it. If we find another operator instead of a literal or a variable name, we need to calculate it first, and its result will be the operand for the previous operator.

With prefix notation, we don’t need to think about priorities anymore because the order of execution is written in the expression itself. A + B * C turns into + A * B C, which means we need to sum A and the result of multiplication of B and C. (A + B) * C turns into * + A B C, which means we need to multiply C and the sum of A and B.

Prefix notation fits really good for recursive execution. Let’s say we have a function

execute(operator, operand1, operand2). Then to calculate + A * B C we need to run this code:

execute('+', A, execute('*', B, C));

To calculate * + A B C we will run this code:

execute('*', execute('+', A, B), C);

Postfix notation

Postfix notation, also know as reverse Polish notation, is when we put the operator after its operands. 1 + 2 becomes 1 2 +, A + B * C becomes A B C * +, (A + B) * C becomes A B + C *.

When we execute an expression in postfix notation, we read tokens one by one. If it’s an operand, then we keep it in memory. If it’s an operator, we get operands from memory, execute the operator, and then put its result in the same memory.

Postfix notation is perfect for stack-based execution. When I wrote that we “keep operands in memory”, I didn’t mention how exactly we do it. Here comes the stack.

Let’s calculate an expression: 9 - 2 * 3. In postfix notation it is 9 2 3 * -. We read tokens one by one. First, we get 9. It’s an operand, so we push it to the stack.

| 9

Next, we read 2. We push it to the stack.

| 9 2

Next, we read 3. We push it to the stack.

| 9 2 3

Now we have *. It’s a binary operator, so we need to get two operands for it. We pop the last two operands from the stack. We have 2 and 3. If we multiply them, we get 6. We need to push the result to the stack.

| 9 6

Next, we read -. It’s a binary operator, and we need to pop two operands from the stack. We have 9 and 6 for it. The result is 3. We push it back to the stack.

| 3

We finished reading the expression, and there are no more tokens. If the expression was correct, then the stack must have exactly one value, and it is the result of the expression.

Abstract syntax trees

Prefix and postfix notations have one disadvantage: they assume that each operator has fixed and known arity (the number of operands). In our examples, it wasn’t a problem because most arithmetic operations are binary; they always have two operands (+, -, *, /, etc.). But what if we have functions with a variable amount of arguments? Functions are just like operators; they are basically the same.

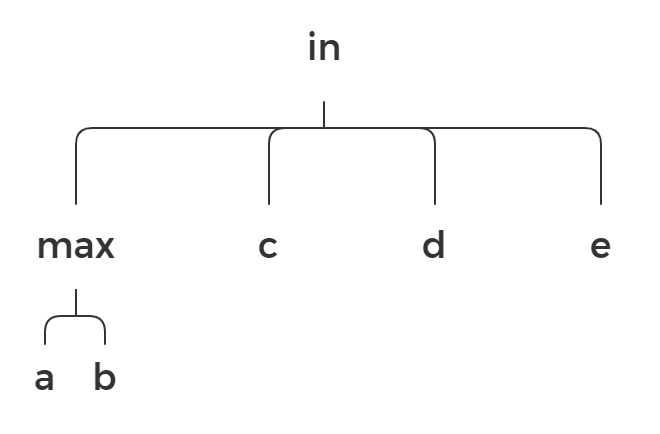

For example, let’s define operators max and in.

max(a, b, c, ...)

a in (b, c, ...)

The max operator returns the max value from the list of its operands. The in operator returns true if its first operand equals at least one of the other operands.

Let’s say we have this expression for whatever reason: max(a, b) in (c, d, e). Here is the prefix notation for it:

in max a b c d e

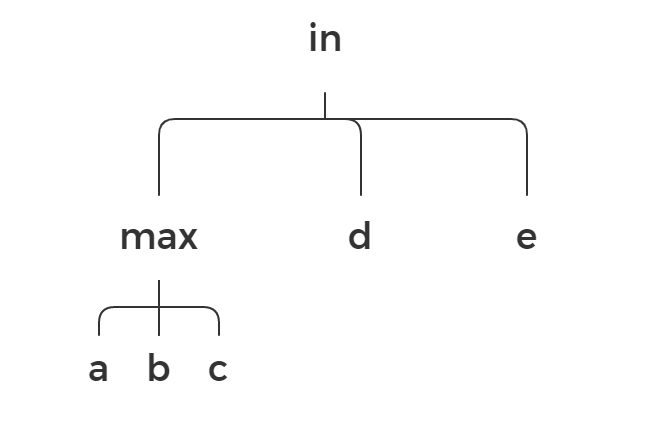

Let’s take another example expression: max(a, b, c) in (d, e):

in max a b c d e

As you might notice, they are the same in their prefix forms. There are possible solutions for it.

Use parentheses

( in ( max a b ) c d e )

( in ( max a b c ) d e )

It solves the problem but makes the implementation of the expression executor more complex. And I can feel some Lisp vibes here.

Pass arity as the first operand

in 4 max 2 a b c d e

in 3 max 3 a b c d e

I like this solution more, but it still feels wrong. Like we lose elegance of Polish notation.

Use non-linear data structures

Instead of using linear notation as we got used to with infix notation, we can go deeper and use another data structure. Our main issue here is that in the line a b c d e, we cannot find what tokens belong to max and what tokens belong to in. But what if we put tokens for different operators into different lines? We can use trees.

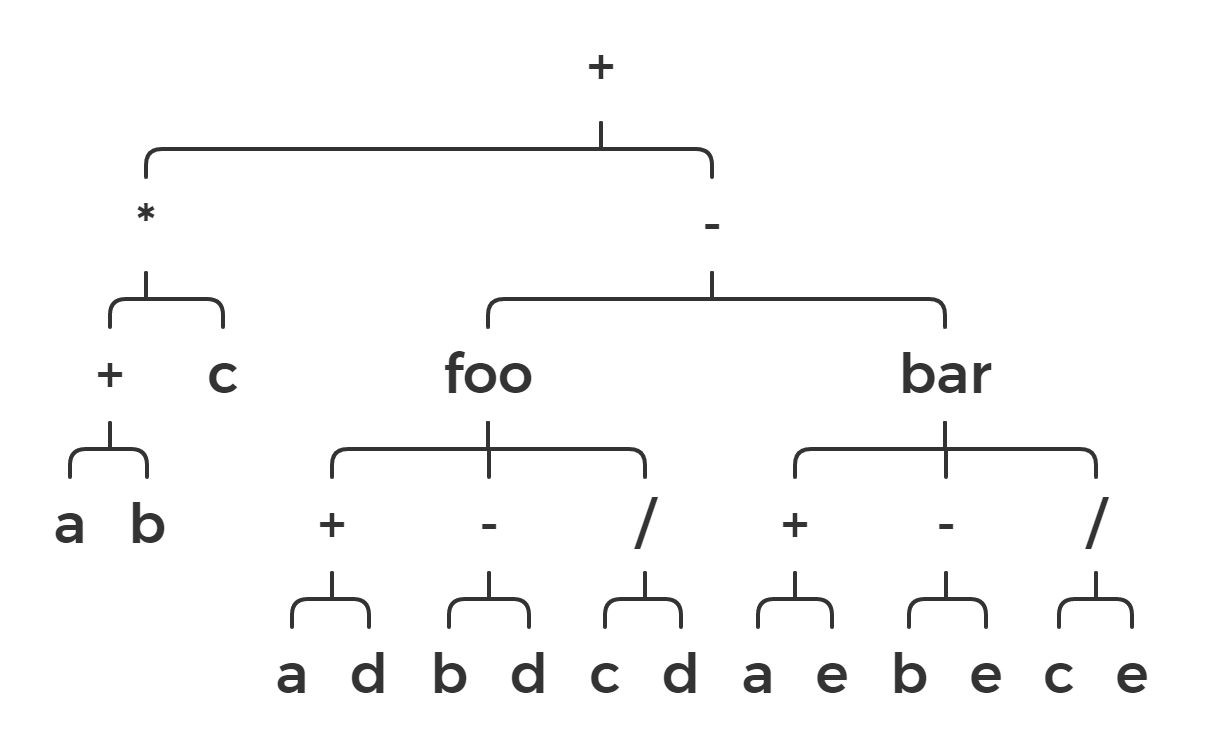

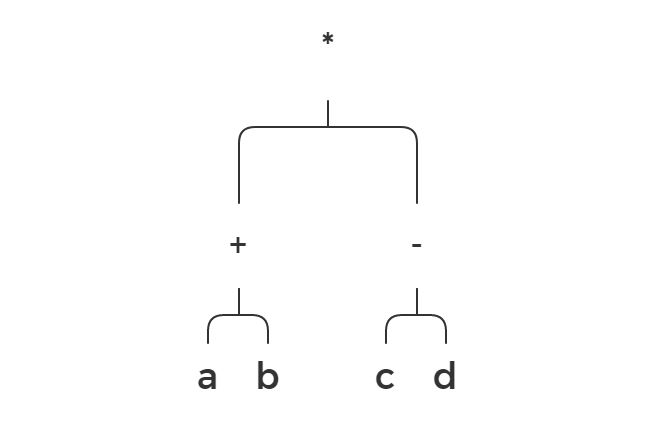

It’s much more clear now where operands for max are and where operands for in are. Let’s take a look at another example: (a + b) * (c - d).

Let’s do a depth-first traversal of this graph and print visited tokens. We will get this result:

* + a b - c d

It is the prefix form of our expression. For this reason, I called these tree structures “prefix trees” when I was working with them. If you search for “prefix trees” in Google, you will find out that prefix trees are something different, and these trees we have here are actually abstract syntax trees (AST). According to Wikipedia, they are used in compilers at one of the syntax analysis stages. It is a good sign for us because we are basically developing a compiler here.

Convert an expression into an abstract syntax tree

The Internet suggests the shunting-yard algorithm to convert an infix-form expression into a postfix form or AST, and it might be a good idea to use it. When I was working on this subject, I used this algorithm as a reference and created my own. The algorithm iterates over the expression’s tokens and inserts them into the tree in the correct position depending on the token’s priority.

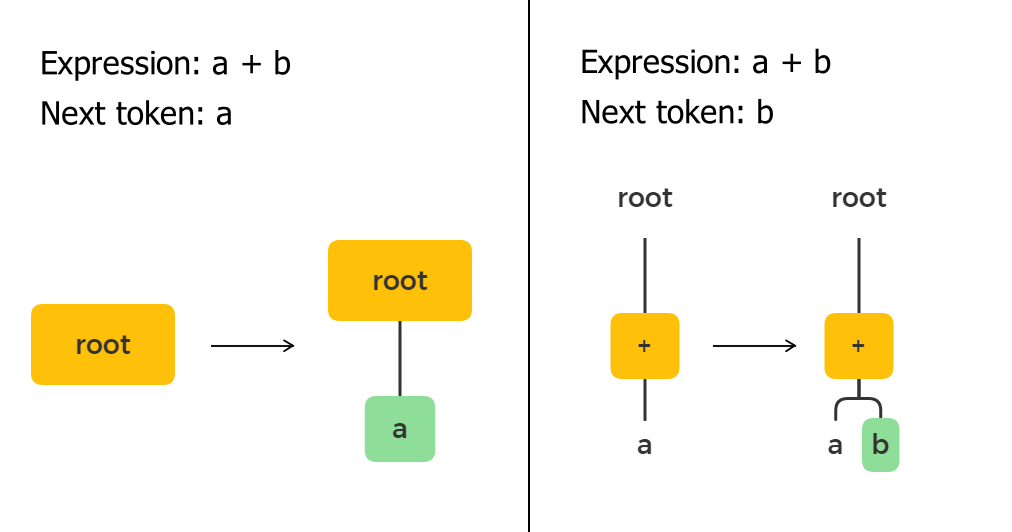

The algorithm keeps a pointer to the current node. In the first step, I create a stub “root” node to avoid nulls. Until we reach the end of the expression, we read tokens, identify their types, and then take different actions depending on the type.

I identify a token’s type in this order:

- if the token is

(, then it’s a left parenthesis; - if the token is

), then it’s a right parenthesis; - if the token is

,, then it’s an argument delimiter; - if the token is on the list of known function, then it’s a function;

- if the token is on the list of known operators, then it’s an operator;

- else it is an operand (a variable name or a literal).

The sorting approach is similar to the shunting-yard algorithm. The insertion actions are different, though.

Operand

If the token is an operand, then we just append it to the current node as a child node. By operands I mean variables and constants, e.g., x, 0, 42, 3.14, “hello”, etc.

Operator

By operators I mean arithmetic and logical operators with at least one operand written on the left side from the operator: +, -, *, in, or, and, comparison operators, etc. We need to compare the priority of the current node’s token with the new token’s priority. Here’s the priority list I use (from lowest to highest):

root, subtree_root, or, -, +, and, /, *, in, >=, >, <=, <, ==, operand

“Root” on the left means no token can be a parent node for the root node. “Operand” on the right means that no token can be a child node for an operand. I’ll explain the “subtree_root” later in this text.

Then actions are different depending on the priorities of the current and the new nodes.

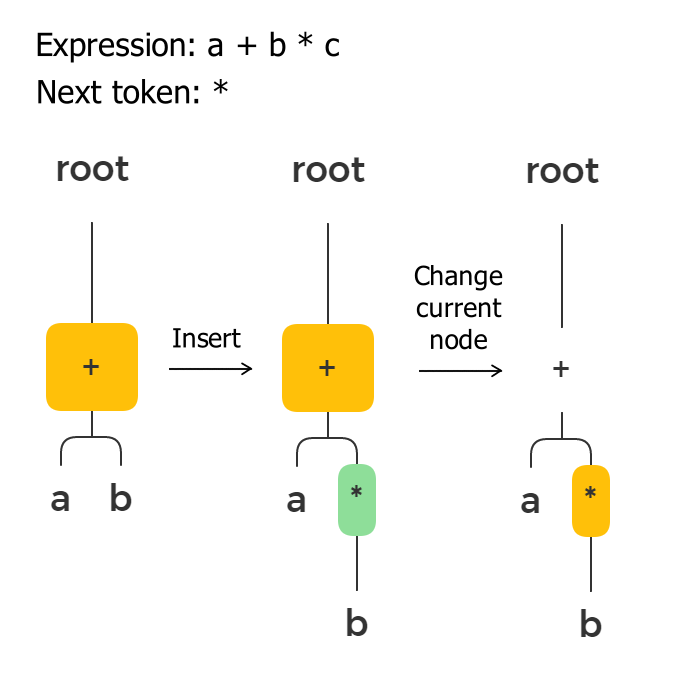

If the new operator’s priority is higher or the same, it must be placed lower in the tree, assuming that the root is on the top (yes, computer trees typically grow from top to bottom). We need to insert this token between the current node and its last child. The last child of the current node becomes the child of the new node, and the new node becomes the child of the current node.

To understand why we insert it as a parent for the last child, we need to remember that we parse infix notation, and we have already read the first operand for this operator. E.g., let’s take a look at the expression: a + b * c. The algorithm reads b before *. It thinks it’s the second operand for + and inserts it as a child for +. Then it reads * and realizes that b must be multiplied before summing, and therefore it moves b to the children of *.

Then we assign the inserted node to the current node pointer because we are reading its operands now.

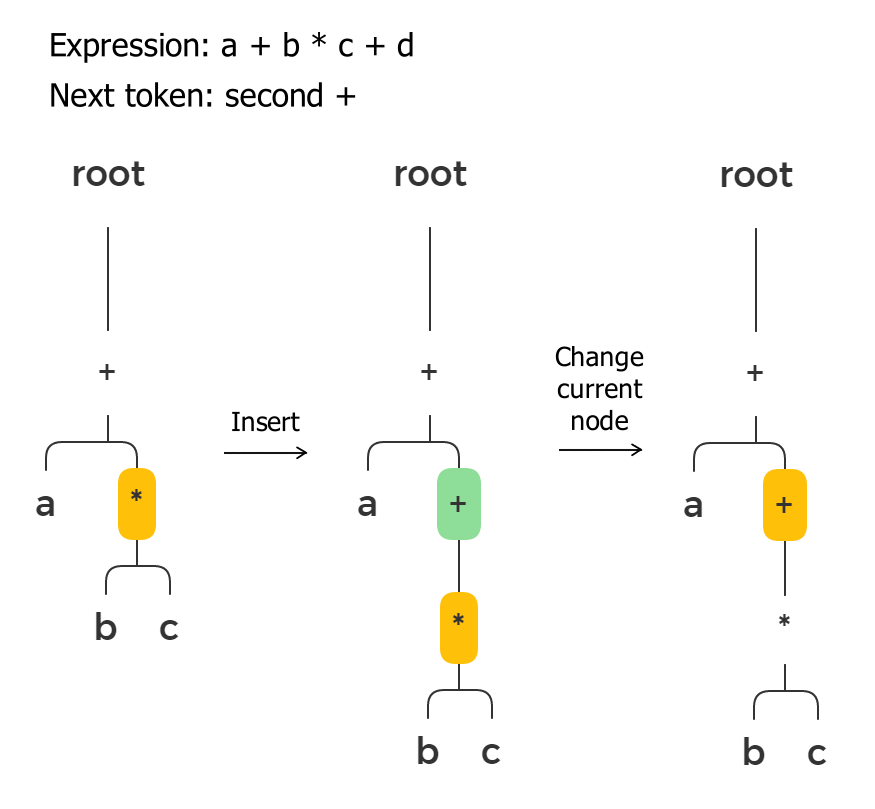

If the new operator’s priority is lower, we need to insert it higher in the tree than the current node. We go up in the tree until we find a node with a priority lower or equal to the new token’s priority. We need to do it because the current node is actually an operand for the new node, so the new node becomes the parent node for the current node.

The root node has the lowest priority, and it guarantees that this upward search will stop if there are no other nodes with lower priority.

Then we assign the inserted node to the current node pointer because we are reading its operands now.

I would say that this approach that I use for operators in this algorithm is similar to the insertion sort algorithm, but for trees.

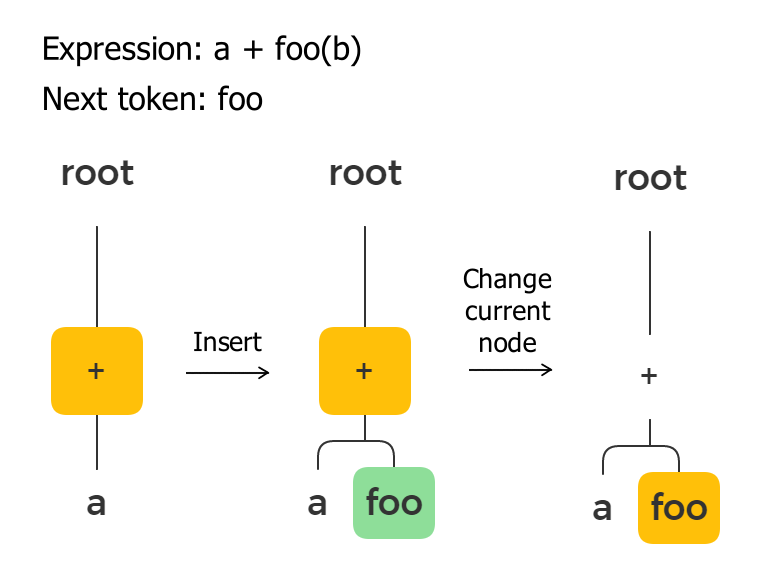

Function

Although I have already mentioned in this article that operators and functions are basically the same, I mean that they are semantically the same. Syntactically they are different, and functions are much easier for the algorithm. First, functions are always written in the prefix-form, i.e., a function name always goes before its arguments. Second, a function’s arguments are always calculated before the function.

max(a + b, c - d)

In this example, we can be sure that a + b and c - d will be executed before max(...).

It means we don’t need to use the priority sorting for functions. We only need to add the function node as a child node to the current node and then assign it to the current node pointer.

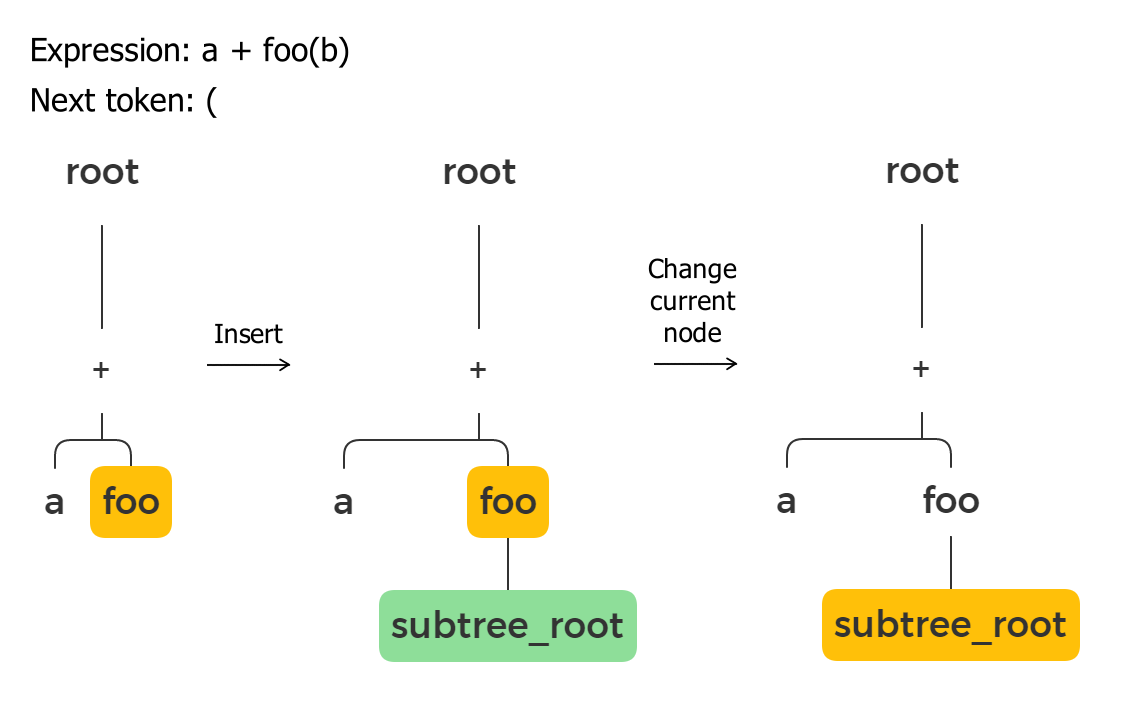

Left parenthesis

Parentheses mean that everything inside them must be executed before the current node. They override the priority sorting. It works both for parentheses we use in mathematical expressions to change the execution order and for functions parentheses. We can use the same approach in both cases.

I use a small hack: I insert a temporary “subtree_root” node with low priority to deal with parentheses. That means that if there will be priority sorting for operators in this subtree, then no node can go outside it because no operator can have priority less than “subtree_root”.

But before it, we need to push the current node to a stack. The current node pointer might be changed during the subtree parsing, and we will need to return to it after we finish parsing the parentheses. Also, the stack guarantees the correct order for nested parentheses.

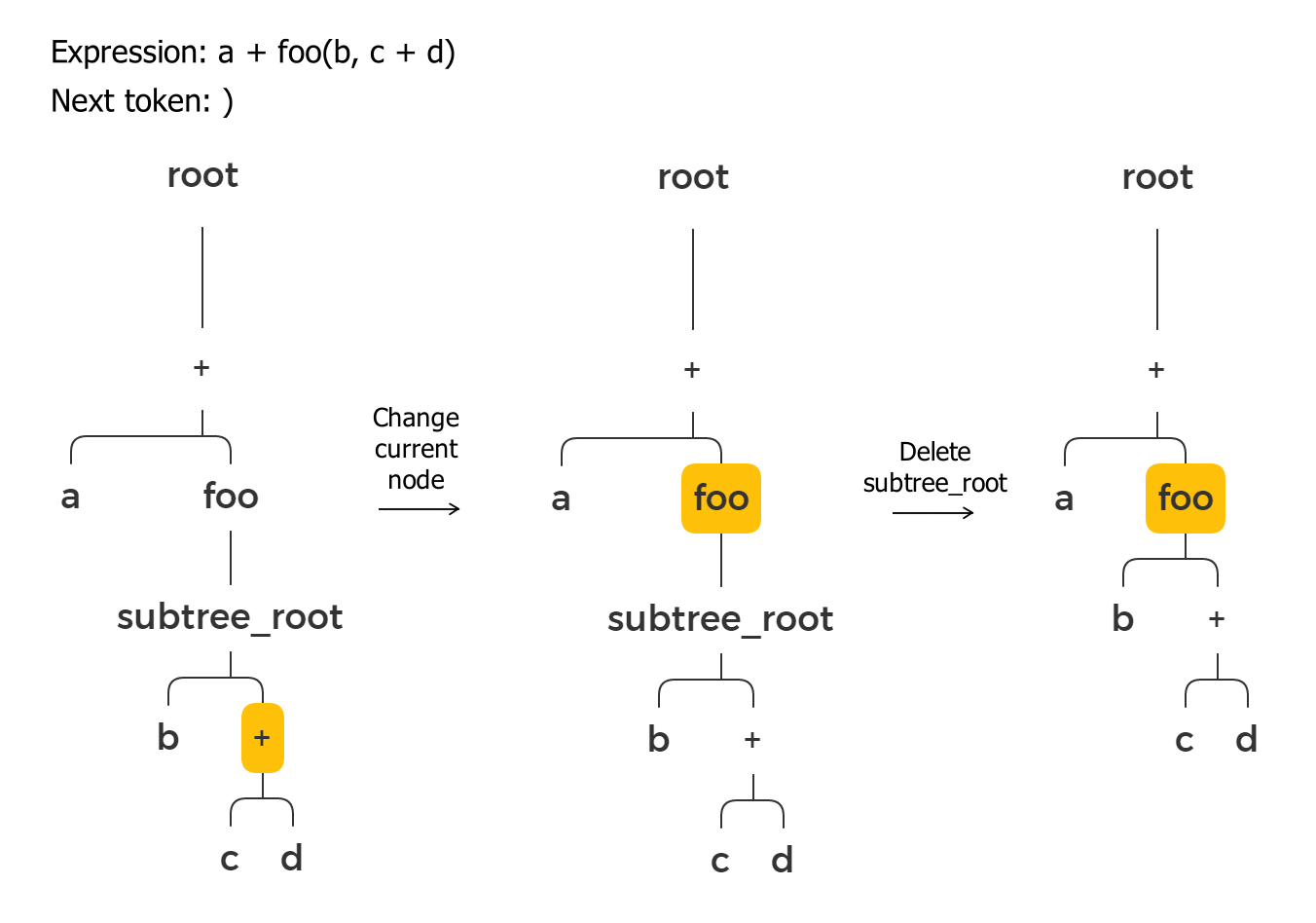

Right parenthesis

A right parenthesis means that the high priority section has ended. We pop a node from the stack and assign it to the current node pointer. We don’t need the “subtree_root” node anymore, so we can delete it and move all its children to the current node.

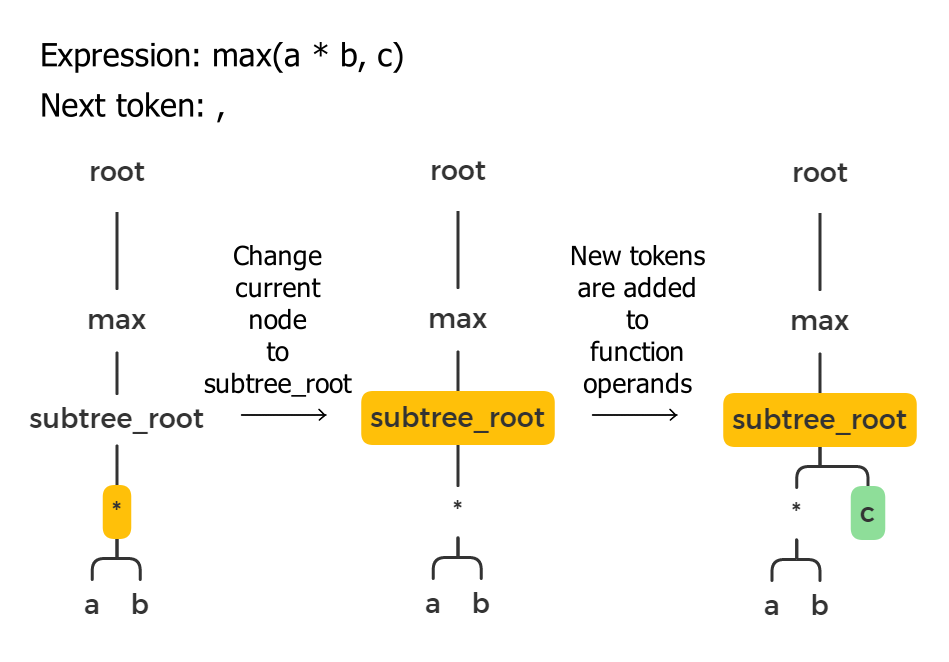

Argument delimiter

Argument delimiters (commas in most cases) split operands for functions (e.g., max(a, b)) and sometimes for operators (e.g., a in (b, c)). They are always used together with parentheses. It means that if we find a comma in an expression, we can assume that we are inside the parentheses block, and therefore there is a “subtree_root” node in the tree.

When we handle subtree operators, the current node can point to an operator in this subtree. When we get the next token after a comma, that token must be added to the subtree_root. We need to go up in the tree until we find the nearest “subtree_root” node and assign it to the current node pointer.

Error handling

Now, when we have an abstract syntax tree, we can check if the expression has any errors. We can iterate over all nodes and check if they are valid. E.g., we can check if the summing node (+) has exactly two child nodes. If we have a programming language with static types, we can verify that all child nodes return compatible types.

Execute an abstract syntax tree

The same execution approach I mentioned for prefix notation works for syntax trees as well. Trees are really good for recursion. To calculate an expression we need to do a recursive depth-first traversal (DFT) of its syntax tree and execute each node. Python-like pseudocode would be like this:

operators = ['+', '-', '*', '/', 'in', ...]

functions = ['max', 'min', 'sin', 'cos', 'round', ...]

def execute(node):

if node.token in operators or node.token in functions:

operands = []

for childNode in node.children:

operands.append(execute(childToken))

result = ... # execute the operator or the function with its operands

return result

else:

return node.token # we might need to parse int from string or do something else here

result = execute(syntaxTreeRootNode)

Operands can be variables. In this case, we need to add context to the executor. The simplest context is a dictionary.

context = {

"x": 2,

"pi": 3.14

}

When we have an operand node, we need to search it in the context. If not found, then it’s probably a constant, and we need to try to parse it from a string.

I don’t add more code examples because the implementation depends on the programming language. I used Python-like pseudocode in this text, but when I implemented this system in a real project, I used Java. With Python, it is easier to work with different types (ints, floats, strings). In Java, I had to implement my own typecasting system to ensure that all nodes return the correct type. It required more work, but I could add compile-time type checks to make sure that we don’t try, for example, to sum an integer and a string.